- Salud animal

- Nutrición animal

- Genético y biodiversidad

- Medio ambiente y recursos naturales

- Socio-economía en sector del cerdo

- Calidad y seguridad del alimento

- Cría y prácticas sostenibles

- Desarrollo rural

water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on growth performance | Effect of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on growth performance of pigs fed a basal diet of broken rice

Castrated male pigs were used in a 2*3 factorial arrangement to study the effect of source of supplementary protein (fresh water spinach, fresh cassava leaves or a mixture [50:50 DM basis] of the two) and DL-methionine on growth performance traits with a basal diet of broken rice (with the permission of Livestock Research for Rural Development).

Introduction

Monogastric animals play an important role in agricultural activities in rural areas in Cambodia. On average, a farmer raises 2 to 5 pigs (local or crossbred). The major problem in pig production is the lack of protein because protein-rich feed resources are scarce and, if available, the prices are often prohibitive. There is therefore a need to identify feeds, which can compensate for these deficiencies.

Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) is a plant that grows equally well in water or in soil. It responds dramatically in biomass yield and protein content when fertilized with biodigester effluent (Kean Sophea and Preston 2003), earthworm compost (Tran Hoang Chat et al 2005) or urea (Li Thi Luyen et al 2004; Tran Hoang Chat et al 2005). In Cambodia, it is cultivated for human food and also is fed to pigs and other animals It does not appear to contain anti-nutritional compounds and has been used successfully for growing pigs as the only source of supplementary protein in a diet based on broken rice (Ly et al 2002). In that research there was a significant response in growth rate and feed conversion to supplementary DL-methionine. Prak Kea et al (2003) reported a linear increase in growth rates in pigs fed water spinach, palm oil and broken rice when up to 6% fish meal (in diet DM) replaced equivalent amounts of water spinach, which they attributed to an improved amino acid balance, especially in terms of the sulphur-rich amino acids.

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is a widely grown crop in many tropical counties (Calpe 1992). Traditionally it is cultivated for root production, but recently attention has focused on managing it as a semi-perennial forage with repeated harvesting at 2-month intervals (Preston 2001). In this system, when the cassava is fertilized with high levels of organic manure, annual protein yields can reach 3 to 4 tonnes/ha.

The protein in cassava leaves has been reported to be rich in lysine but limiting in methionine (Eggum 1970). Water spinach also appears to be limiting in methionine in view of the growth response when synthetic DL-methionine was added to a diet in which water spinach provided most of the protein (Ly et al 2002). Mixing two sources of leaves as sources of protein may be beneficial in view of possible complementary effects of the two arrays of amino acids.

The aim of the present experiment was to study the effect of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves, fed alone or mixed together, on growth performance of pigs fed a basal diet of broken rice, with or without a supplement of DL-methionine.

Material and Methods

Location

The experiment was carried out from 16 November 2004 to 24 February 2005 in the Center for Livestock and Agriculture Development (CelAgrid-UTA Cambodia), located in Kandal village, Rolous Commune, Kandal steung district, Kandal province about 25km from Phnom Penh City, Cambodia .

Experimental animals, treatments and design

Eighteen crossbred (Local*Landrace or Local*Duroc) castrated male pigs with initial body weight from 11 to 14 kg were allocated to 6 treatments in a 2*3 factorial arrangement. The factors were:

Methionine:

- With (M)

- Without (NM)

Protein supplement:

- Fresh cassava leaves (CL)

- Fresh water spinach (WS)

- Mixture of cassava leaves and water spinach (50: 50 DM basis) (WSCL)

The pigs were allocated into 3 blocks according to live weight and the nutritional treatments were applied at random within each block. The pigs were housed in individual pens with concrete floor and provided with feeders and drinking nipples. The pigs were vaccinated against Salmonella disease and were adapted to the feeds and the housing for a 10 day period before starting the experiment.

Feeding and management

Broken rice is a by-product of Cambodian rice mills and was available in the local market. Premix and methionine were purchased from shops in the city. Fresh cassava leaves were harvested every day from plots in CelAgrid (Photo 1). The water spinach was purchased from traders who harvested it from lagoons receiving waste water from Phnom Penh city (Photo 2).

Photo 2: Water spinach being harvested in the lagoon

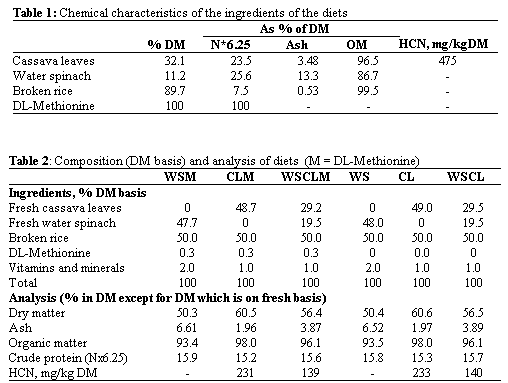

The leaves plus stems of the water spinach and the leaves of cassava (after removing stems and petioles) were chopped into small pieces, mixed with the other ingredients of the diet (Tables 1 and 2) and fed immediately. The amounts of feeds offered were based on the broken rice being fed at the rate of 2 kg DM per 100 kg live weight (equivalent to 4 kg of DM per 100 kg live weight of the total feed), and were given in 3 meals daily (8.00, 12.00 and 17.00h).

Data collection and analyses

The pigs were weighed every 10 days until 100 days. Individual daily weight gains were calculated by the regression of live weight on time in days. Individual feed intake and crude protein intake were recorded daily from weight of fresh material offered minus the residue collected the next morning. Feed conversion ratio was calculated from individual daily DM intake and live weight gain. Feed samples were taken every 5 days to determine DM and every 10 days for N and HCN. The DM content was determined using the microwave method of Undersander et al. (1993). Ash, N and HCN were analysed following procedures of AOAC (1990).

Statistical analysis

Data for weight gain, feed DM intake, crude protein intake and feed conversion were analysed using the general linear model (GLM) option of the ANOVA software of Minitab (2000). The sources of variation were blocks, diets, methionine, interaction diets*methionine and error.

Results and discussion

Feed intake

The intake of the water spinach (as DM) was almost twice that of the cassava leaves (84% higher) when each was given separately and resulted in an associated (since all ingredients were mixed together) greater intake of the broken rice, and thus of total DM (Table 3). Intakes of total foliage on the mixed supplement (WSCL) were slightly above the mean value for each foliage given alone. As the content of crude protein was similar in the cassava leaves and the water spinach, intakes of crude protein followed those of the DM. The foliages supplied from 38% (cassava alone) to 49% (water spinach alone) of the total DM intake and from 65 to 75%, respectively, of the crude protein intake.

Addition of methionine to the diets led to a lower intake of broken rice, a higher intake of cassava leaves and no change in water spinach intake. The overall effect was a slightly higher (6%) intake of DM as a function of live weight. Total crude protein intake was not affected by methionine supplementation but the proportion of the total diet DM as forage and of total diet protein from foliage protein was higher with methionine supplementation. There appeared to be an interaction between methionine supplementation and the source of forage protein (Figure 1), with no differences in the proportions of protein derived from the foliage on the diets of cassava leaves and water spinach as separate supplements but a 25% increase on the mixed foliage diet.

Growth and feed conversion

There were no ill-health symptoms in any of the pigs that could have been ascribed to HCN toxicity. On a live weight basis the HCN levels consumed on the CL and WSCL diets (6.28 and 4.86% of LW) were considerably higher than the maximum levels recommended by other authors, which were 1.4 (Getter and Baine 1938), 2.1 to 2.3 (Johnson and Ramond 1965), 3.5 (Tewe1992) and 4.4% of LW (Butler 1973).

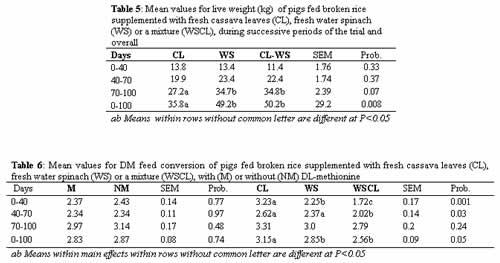

There were marked differences in growth rate due to the source of supplementary protein (Table 4; Figure 2). Supplements containing water spinach supported higher growth rates compared with cassava leaves alone. Growth rates on the mixture of water spinach and cassava leaves were similar to those on water spinach alone and considerable higher than the average of cassava alone and water spinach alone. Data for feed conversion rate (Table 6 and Figure 3) showed a similar trend with the differences in favour of the mixed foliages being more marked than in the case of live weight gain. The implication from these findings is that there was a synergistic effect from combining the two sources of protein, presumably because of a superior array of essential amino acids in the mixture compared with either supplement fed alone. For all supplements, growth rates increased and feed conversion improved as the trial progressed, with consistent (over 50%) differences in favour of the diets containing water spinach. Trends for live weight at the end of each period were similar to those for growth rate (Table 5).

Supplementation with DL-methionine had no effect on growth rate or feed conversion in any of the periods of the trial (Table 4). This result was unexpected as in a similar trial with broken rice and water spinach there was a significant improvement in growth rate due to methionine supplementation (Ly et al 2002). Significant improvements in growth and feed conversion when DL-methionine was added to diets containing ensiled cassava leaves were also reported by Nguyen Thi Hoa Ly (2005).

A lower consumption of broken rice, of total DM and of crude protein (Table 6) would appear to be the reason for the lower growth performance of pigs fed only the cassava leaves as protein supplement. The intake of crude protein appeared to be the critical factor, and accounted for 92% of the variation in growth rate (Figure 4).

According to Ravindran et al (1987), the bitter taste of the cassava leaves could negatively influence their intake by pigs. The presence of tannins in the may also have reduced intake. However, such potential effects of the non-nutritional compounds does not explain why DM intake on the mixture of water spinach and cassava leaves was the same (in fact slightly though not significantly higher) as on water spinach alone, when the expectation was that it should be midway between the values for each foliage given separately.

DM intake as a percentage of live weight over the overall period of 0-100 days for the CL diet (3.31%) was the same as was reported by Chhayty et al (2005) (3.30%) for the same feeds in a digestibility trial and similar to that reported by Du Thanh Hang (2005) (range of 2.7 to 3.3%) for crossbred pigs fed a 2:1 mixture of ensiled cassava root and rice bran and fresh cassava leaves that had been washed prior to feeding. It was higher than the values reported by Nguyen Duy Quynh Tram (2003) and Bounhong et al (2004) (2.6 and 3.11%, respectively), who used the same diet as in the present study. However, a much higher intake (4.4% of live weight) was recorded for pigs fed broken rice and cassava leaves that had been ensiled before feeding (Chhay Ty et al 2003a). It would appear that ensiling the leaves increases their palatability; however, a comparison of fresh versus ensiled leaves in the same experiment does not appear to have been made. Also, in the experiment of Chhay Ty et al (2003), 3% of dried fish was in the diet and the pigs weighed only 9 kg. Both these differences could have accounted for the higher DM intakes as a percentage of live weight.

Conclusion

In a feeding system for growing pigs (LW range 11 to 50 kg), with broken rice as the only other ingredient restricted to 2% of LW, and with supplements of water spinach, fresh cassava leaves or a mixture (50:50 DM basis) of the two:

- Fresh cassava leaves supplied up to to 40% of the DM without apparent signs of toxicity of HCN.

- Fresh water spinach was eaten in greater quantities than fresh cassava leaves, when compared on a DM basis.

- The mixture of leaves was eaten in similar amounts (of DM) as for water spinach as the only supplement.

- The growth and conversion rates were 50% better for the diets with water spinach alone, or as a mixture with fresh cassava leaves, compared with fresh cassava leaves alone.

- There appear to be synergistic positive effects from combining two sources of protein-rich leaves as supplements to a low protein basal diet.

- Performance was not affected by supplementation with DL-methionine.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the MEKARN project financed by the SIDA-SAREC Agency,and to the Center for Livestock and Agriculture Development (CelAgrid UTA-Cambodia), for providing resources for conducting this experiment

References

- AOAC 1990. Official Methods of Analysis. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 15th Edition (K Helrick editor). Arlington pp 1230

- Bounhong Norachack, SoukanhKeonouchanh, Chhay Ty, Bounthong Bouahom and Preston T R 2004: Stylosanthes and cassava leaves as protein supplements to a basal diet of broken rice for local pigs. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Vol. 16, Art. # 74. Retrieved , from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd16/10/boun16074.htm

- Butler G W 1973 Physiological and genetic aspects of cyanogenesis in cassava and other plants, Chronic cassava toxicity. Proceedings of the Interdisciplinary Workshop, London England, 29-30 Jan., 1973. IDRC -010e, pp. 65-71

- Calpe C 1992 Root, tubers and plantains: recent trends in production trade and use. In: Machin F and Nyvild S (Editors) Root, tuber, Plantains and Bananas in Animal Feeding. FAO Animal Production and Health Paper 95, pp. 11-25

- Chhay Ty, Preston T R and Ly J 2003: The use of ensiled cassava leaves in diets for growing pigs. 2. The influence of type of palm oil and cassava leaf maturity on digestibility and N balance for growing pigs. Livestock Research for Rural Development 15 (8). Retrieved June 30, 2005, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd15/8/chha158.htm

- Chhay Ty and Preston T R 2005: Effect of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on intake, digestibility and N retention in growing pigs. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Vol. 17, Art. #23. Retrieved June 30, 2005, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd17/2/chha17023.htm

- Du Thanh Hang and Preston T R 2005 The effects of simple processing methods of cassava leaves on HCN content and intake by growing pigs. Proceedings of Workshop-seminar "Making better useof local feed resources" MEKARN-CTU, Cantho, 23-25 May, 2005. http://www.mekarn.org/procctu/hang.htm

- Eggum B O 1970 The protein quality of cassava leaves. British Journal of Nutrition. 24: 761-768

- Getter A O and Baine J 1938 Research on cyanide detoxification. American Journal of Medical Science. pp. 185-189

- Johnson R M and Ramond W D 1965 The chemical composition of some Tropical food plants: Manioc. Tropical Science 7, pp. 109-115.

- Kean Sophea and Preston T R 2001 Comparison of biodigester effluent and urea as fertilizer for water spinach vegetable. Livestock Research for Rural Development 13 (6) http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd13/6/kean136.htm

- Ly Thi Luyen and Preston T R 2004: Effect of level of urea fertilizer on biomass production of water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) grown in soil and in water. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Vol. 16, Art. #81. Retrieved , from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd16/10/luye16081.htm

- Ly J, Hean Pheap, Keo Saeth and Pok Samkol 2002. The effect of DL-methionine supplementation on digestibility and performance traits of growing pigs fed broken rice and water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica). Livestock Research for Rural Development (14) 5: http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd14/5/ly145b.htm

- Ly J 2002 The effect of methionine on digestion indices and N balance of young Mong Cai pigs fed high levels of ensiled cassava leaves. Livestock Research for Rural Development. (14) 2: http://www.cikpav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd14/6/Ly146.htmMINITAB 2000 Minitab Reference Manual release 13.31.

- Nguyen Duy Quynh Tram and Preston T R 2004: Effect of method of processing cassava leaves on intake, digestibility and N retention by Ba Xuyen piglets. Livestock Research for Rural Development.Vol. 16, Art. # 80. Retrieved , fromhttp://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd16/10/tram16080.htm

- Prak Kea, Preston T R and Ly J 2003 Feed intake, digestibility and N retention of a diet of water spinach supplemented with palm oil and / or broken rice and dried fish for growing pigs. Livestock Research for Rural Development (15) 8 Retrieved , from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd15/8/kea158.htm

- Preston T R 2001 Potential of cassava in integrated farming systems. . International Workshop Current Research and Development on Use of Cassava as Animal Feed, Khon Kaen, Thailand July 23-24, 2001. http://www.mekarn.org/procKK/pres.htm

- Ravindran V, Kornegay E and Rajaguru E S 1987 Influence of processing methods and storage time on the cyanide potential of cassava leaf meal. Animal Feed Science and Technology 17:227-23

- Tewe O O 1992 Detoxification of casava products and effecs of residual toxins on consuming animals. In: Roots, tubers, plantains and bananas in animal feeding. (D. Machin and S. Nyvold, editors) FAO Animal Production and Health Paper No 95. Rome p 81-98

- Tran Hoang Chat, Ngo Tien Dung, Dinh Van Binh and Preston T R 2005 Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) as replacement for guinea grass for growing and lactating rabbits; Workshop-seminar "Making better use of local feed resources" (Editors: Reg Preston and Brian Ogle) MEKARN-CTU, Cantho, 23-25 May, 2005. Article #48. Retrieved , from http://www.mekarn.org/proctu/chat48.htm

- Undersander D, Mertens D R and Theix N 1993 Forage analysis procedures. National Forage Testing Association. Omaha pp 154

Citation of this paper

Comentarios

CIRAD © 2007 (Derechos reservados) - Legales informaciones - Actualizaión de la pagina : 13/04/2007